A brief examination of the court structure of England and Wales since the introduction of the Supreme Court

Government lawyers who have read of the recent “Brexit” cases1 before the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom may wonder where this court fits into the UK court hierarchy, having never heard of it while reading law at university.

This note offers assistance to government lawyers who wish to understand the current hierarchy of the courts of England and Wales, and how those courts fit into the national hierarchy of the United Kingdom.

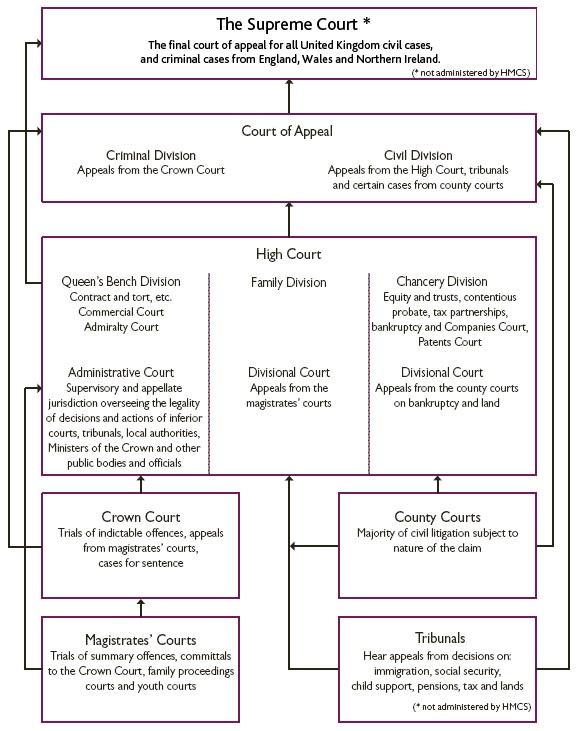

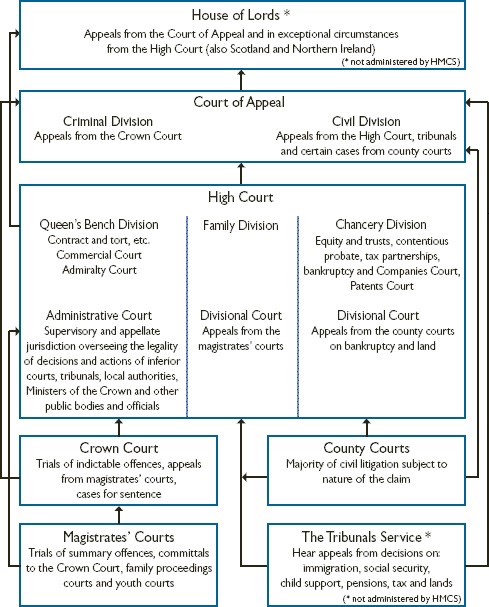

Diagram of current and old structure/hierarchy

As currently formulated

As formulated before 2009

History

Separation of powers is not entrenched in the British Constitution as it is in other countries, and for that reason the UK Parliament and its officers have historically had not only legislative but also executive functions. For example, the office of Lord Chancellor had functions of all three kinds.

The Supreme Court was established by the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 (UK) and commenced operation in 2009, primarily to separate more clearly judicial from legislative functions.

As appears from the diagrams, the Supreme Court is, in many ways, the successor to the former judicial function of the House of Lords. Those were the hearing of appeals to the Queen-in-parliament (the Crown in its legislative role) by the Lords of Appeal in Ordinary (colloquially called Law Lords) comprising the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords –(in legal contexts colloquially called the House of Lords). The House of Lords in that sense should not be confused with the House of Lords as the upper house of the United Kingdom’s Parliament.

The Supreme Court also has taken on some of the functions of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, primarily so-called ‘devolution’ matters relating to the devolved administrations of Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales. The Privy Council continues its former role as the final court of appeal from British colonies and former colonies.

The Constitutional Reform Act also transferred the roles of the Lord Chancellor as president of the House of Lords to the new Lord Speaker, and as head of the judiciary in England and Wales and presiding judge of the High Court of Justice to the Lord Chief Justice. The Lord Chancellor retains her executive functions as member of the Privy Council and the Cabinet and head of the Department of Constitutional Affairs.

The Act also altered the process for the appointment of judges. Members of the Supreme Court are now styled ‘Justices’ and will still be referred to as my Lord or my Lady, but will not sit as Peers in the House of Lords. The Court consists of a President (currently Lord Neuberger of Abbotsbury), a Deputy President (Baroness Hale of Richmond) and nine other Justices.

The Supreme Court should not be confused with the former Supreme Court of England and Wales (known as the Supreme Court of Judicature until 1981) established under the 19th century Judicature Acts, which consisted of the Court of Appeal, the High Court of Justice and the Crown Court. Those courts continue in existence but are now known collectively as the Senior Courts of England and Wales.

Modern avenues of appeal

Avenues of appeal to the Supreme Court remain much the same as they were to the House of Lords. That is to say, that the Supreme Court is the highest appellate court in the UK. Thus, appeals ordinarily come from the Court of

Appeal in both its civil and criminal divisions.

Additionally, appeals may come directly from the High Court (constituted either as a divisional court as in the Brexit case, or by a single judge), bypassing the Court of Appeal in certain circumstances.

For Scotland, civil appeals come from the Court of Session, but the High Court of Justiciary remains the court of final appeal in criminal matters. For Northern Ireland, appeals come from the Court of Appeal in Northern Ireland in both civil and criminal jurisdiction.

Leapfrog appeals within the hierarchy

At this point, it all seems fairly straight forward. However, not all avenues of appeal to the Supreme Court need to be through each court in the hierarchy.

Section 40 of the Act provides that “[a]n appeal lies to the Court from any order or judgment of the Court of Appeal in England and Wales in civil proceedings... only with the permission of the Court of Appeal or the Supreme Court…” The permission of either court can of course only be given where there is no “provision under any other enactment restricting such an appeal.”

Additionally, appeals may come directly from the High Court (constituted either as a divisional court as in the Brexit case, or by a single judge), bypassing the Court of Appeal in certain circumstances.

So how do appeals from the High Court of England and Wales and the High Court in Northern Ireland proceed to the Supreme Court?

These appeals are often called leapfrog appeals. They are only possible subject to sections 12 to 16 of the Administration of Justice Act 1969.

A certificate of the trial judge, which must be given if a sufficient case for has been made for leave to appeal, can be granted for any civil proceedings before a single judge of a High Court or a Divisional Court. The certificate can be granted only if a point of law of general public importance is involved and may only be granted on immediate application to the judge after judgment is given in the proceedings2. No appeal lies against the grant or refusal of the judge’s certificate.

Either party to the proceedings may then, within one month of receiving the judge’s certificate, apply for leave to appeal to the Supreme Court. The application is heard on the papers, where granted, annuls the right to appeal to the Court of Appeal.

1 R (Miller) v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union [2017] UKSC 5; [2017] 2 WLR 583; [2017] 1 All ER 593, on appeal from [2016] EWHC 2768; [2017] 1 All ER 158.

2 Section 12(3). Such a point of law relates to either the construction of an enactment or instrument and has been fully argued in the proceedings, or is one in which the Judge was bound by the decision of a superior court (the Court of Appeal or Supreme Court) and so it may be appealed to a higher authority.

The information in this publication is provided for general purposes only. It is not to be relied on as a substitute for legal advice. Crown Law and the Department of Justice and Attorney-General accept no liability for losses caused by reliance on the material in this publication. Formal legal advice should be obtained for particular matters.

Published: 14 June 2017

Author: Lawyer, Tarquin Nesbitt-Foster