CASE NOTE – BROCKHURST V RAWLINGS [2021] QSC 217

Key points:

- Evidence of a plaintiff’s prior dishonesty may not result in an adverse credibility finding.

- Arguments about forensic disadvantage due to delay may be defeated where there is corroborating evidence.

- Substantial awards for economic loss (and interest on past economic loss) may be made where the plaintiff can demonstrate a drive for employment.

- Pre-existing conditions such as oppositional defiance disorder may not affect economic loss awards where there is no evidence of such behaviours being exhibited after leaving school.

Background

In 1996 and 1997, a teacher at Toowoomba Grammar School engaged in an intimate relationship with her then 13-year-old student, Mr Nicholas Brockhurst. The teacher, Mrs Rawlings, denied the relationship was sexual or romantic but admitted it was “complicated” with “fuzzy boundaries”. Mrs Rawlings resigned upon the headmaster of the school questioning her about the relationship, and at that time terminated her affair with Mr Brockhurst.

Mr Brockhurst struggled with depression after the break-up. He claimed damages against Mrs Rawlings for trespass by battery. He also made a claim against Toowoomba Grammar School, however this claim was settled out of court prior to the litigation against Mrs Rawlings.

Issues for the court

In this decision, Justice Ryan was required to determine the following issues:

- Did Mrs Rawlings sexually abuse Mr Brockhurst?

- Where it was agreed that Mr Brockhurst had pre-existing oppositional defiance disorder, did the abuse cause his ongoing mental health issues?

- The damages assessment.

Did Mrs Rawlings sexually abuse Mr Brockhurst?

Consent

At the outset, the court noted the fact any sexual activity was “consensual” was of no consequence. This was because Mr Brockhurst was incapable of voluntarily consenting to the activity due to his age.

Allegations of abuse

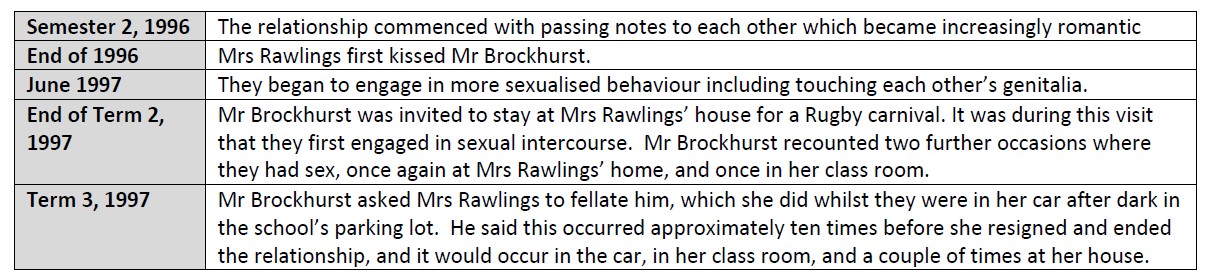

The alleged timeline of activity between Mr Brockhurst and Mrs Rawlings was as follows:

Corroborating evidence

In April 1997, Mr Brockhurst and Mrs Rawlings were seen by other school students having close physical contact which would not be consistent with an appropriate relationship. Contemporaneous statements given by the students to the school were available in evidence, and three of the four students were able to give oral evidence at the trial.

Mr Brockhurst’s parents were also able to give oral evidence as they had observed interactions between him and Mrs Rawlings as well as the notes that passed between them.

Mr Brockhurst’s Credit

Justice Ryan accepted Mr Brockhurst as a truthful witness. This was despite the defence alleging inconsistencies in his evidence (which were readily explained away) and prior incidents of dishonesty including pleading guilty to fraud when he was 16 or 17 and lying on Defence Force applications.

Whilst the court accepted this conduct went against his credit, Justice Ryan concluded the lies were ones told by a man suffering emotionally who was trying to reset. Viewed that way, they did not detract from the credibility of his sworn testimony about the grooming, abuse, and the aftermath.

Further, any failure to report the abuse when Mr Brockhurst was referred to a psychiatrist was not evidence that the abuse did not occur. The theory that a “genuine” victim of sexual abuse would complain at the “first reasonable opportunity” has long been debunked.

Mrs Rawlings’ denial

Mrs Rawlings adamantly denied any sexual activity occurred or that the relationship was romantic. Relevantly she argued:

- The messages she gave to Mr Brockhurst were messages of support in the context of behaviour management.

- She could not have had sex with Mr Brockhurst at her house as her husband and father-in-law were also there at that time and there would have been no opportunity.

- She did not park in the space where Mr Brockhurst alleged that she fellated him, and she would not have had any opportunity to engage in sexual activity there as people would see them.

The court did not accept Ms Rawlings’ submissions. Of relevance, the content of the messages could not have plausibly related to a behavioural modification program. Further, there was no evidence proving there was no time at which Mrs Rawlings and Mr Brockhurst were not alone at her house. Finally, the fact Mrs Rawlings may have parked in a different parking spot was of no real consequence as she still had the opportunity to engage in the conduct complained of after dark when there were few people walking around.

Whilst the court accepted that the delay since the abuse would cause some forensic disadvantage, Justice Ryan concluded any concern about this was alleviated by the fact the plaintiff had corroborating evidence.

Liability conclusion

Ultimately the court found in favour of Mr Brockhurst as his accusations were not in vague terms, his account included details which added to his credibility, and there was corroborating contemporaneous evidence. The court concluded Mrs Rawlings was not a witness of truth as some of her evidence was implausible and contradicted by her own correspondence and other credible evidence independent of the plaintiff.

Did the abuse cause Mr Brockhurst’s ongoing mental health issues?

Dr Evans and Dr Leong, psychiatrists called by Mr Brockhurst, both concluded the abuse had an impact on Mr Brockhurst’s education and his academic outcome, which in turn affected the course of his work life and earning capacity. Dr Leong, however, concluded there would be no future impact.

Dr Chalk, psychiatrist called by the defendant, concluded that if Mr Brockhurst’s account was accepted, the alleged abuse could well have led to an aggravation of underlying difficulties.

The defence argued that the plaintiff’s condition was pre-existing as he had exhibited oppositional defiance disorder prior to the alleged abuse. However, the evidence of Mr Brockhurst’s academic performance showed a decline which coincided with the development of the abusive relationship. Further, the court concluded an oppositional defiance disorder would not explain his later desire to retreat from the world, flashbacks, issues with sexual intimacy or insomnia.

Accordingly, Justice Ryan held that the abuse did cause Mr Brockhurst’s ongoing mental health issues, including persistent depressive disorder. Further, the oppositional defiance disorder was not treated as significant as both Drs Chalk and Evans acknowledged this condition did not necessarily evolve into an adult condition, and there was virtually no evidence of any such behaviours after Mr Brockhurst left school.

Damages assessment

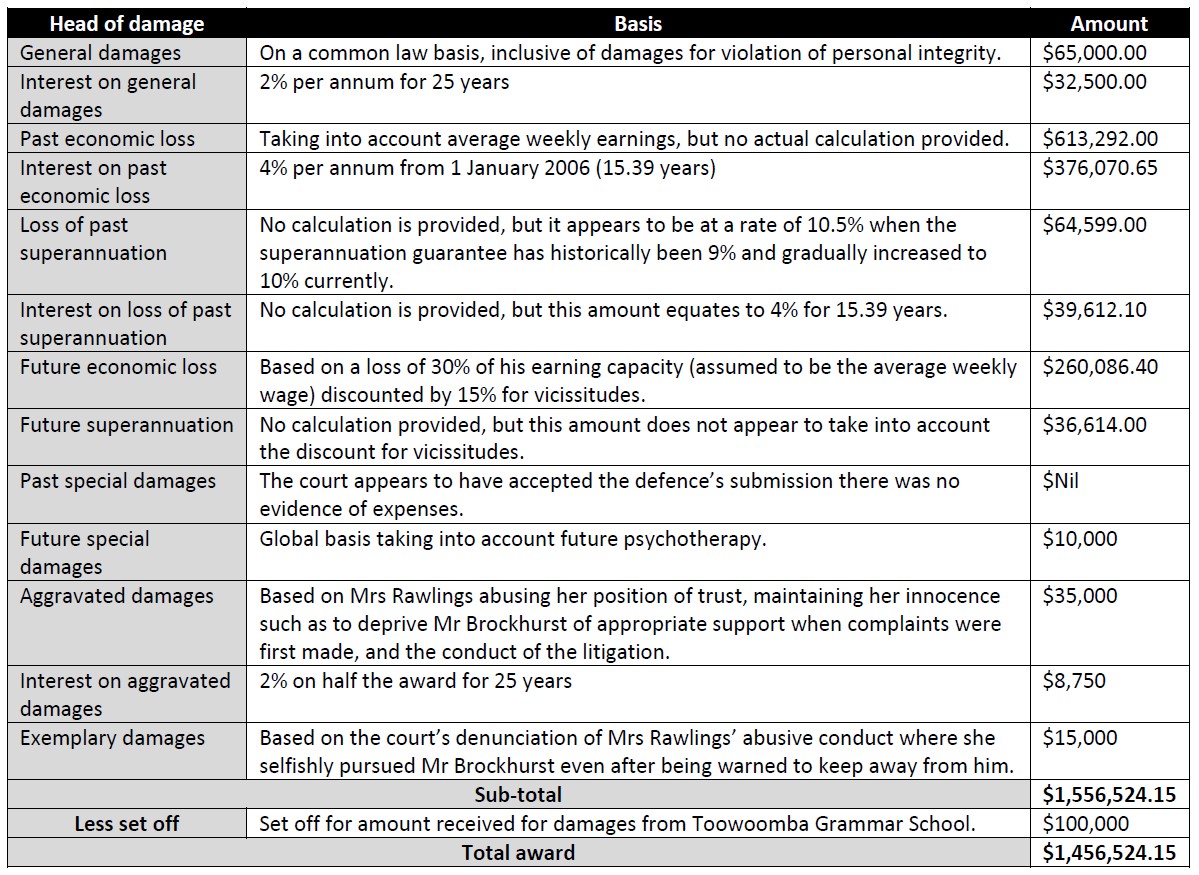

The court awarded damages as follows:

General damages

The general damages award accounted for Mr Brockhurst’s age at the time of the abuse and evidence of his suffering. Justice Ryan acknowledged the decision in B v Reineker [2015] NSWSC 949 where general damages were assessed at $350,000. Justice Ryan also noted P v R [2010] QSC 139 where $80,000 was awarded for general damages and said this aligned with the assessment in BDT v BDG [2019] QDC 74.

Economic loss

Justice Ryan was not prepared to accept that in the absence of the abuse, Mr Brockhurst would have completed a Bachelor of Engineering, but did accept he may have completed some four years of further study. As there was limited evidence about Mr Brockhurst’s future prospects (noting primary school results were not necessarily a reliable indicator), Justice Ryan proceeded on the basis Mr Brockhurst would have earned the average weekly wage for males in Australia. This assumption was based on Mr Brockhurst demonstrating he had been driven to find employment when not overwhelmed by the symptoms of his psychiatric injury. The relevant evidence in this regard included Mr Brockhurst’s actual employment history, attempts to join the Defence Force, the fact he had obtained work with relative ease, and that he had never been terminated by his employer (with one exception involving a Spanish medical certificate).

Justice Ryan found Mr Brockhurst’s past inability to obtain employment and hold down a job for any length of time were consequences of the psychological injury caused by the abuse, and he would suffer a reduction in his earning capacity for the rest of his working life because of the abuse. Justice Ryan further noted while the end of the litigation might reduce Mr Brockhurst’s tendency to ruminate on the abuse, it is likely he will never be free of the consequences, and future therapy may trigger discomfort or distress which will impact negatively on his ability to work.

Conclusion

This decision highlights the fact certain inconsistencies and previous instances of dishonesty on the part of a plaintiff will not necessarily result in a finding they are not a credible witness. Further, evidence concerning lack of opportunity must amount to more than the possibility of being seen and should include evidence from independent witnesses.

With respect to damages, this is another instance where past interest has formed a significant portion of the total award. Notably, Mr Brockhurst’s award for economic loss was also significant as he was able to demonstrate he would have had a consistent earning history in the absence of the abuse. Had he not been able to sufficiently evidence his drive for employment, it is likely the award would have been more limited.

Published: 3 September 2021

Author: Rebecca Reeves